How to give and get better support

Rethinking Support: Unpacking the concept of ‘scaffolding’

Rethink is a newsletter for curious minds and life-long learners. If you love it, why not consider supporting it for only $7/£6 a month. Thank you!

Dear Rethinkers,

We all need support to achieve things, yet some of us are better at asking for it than others. Do you invest enough time in looking for the right kind of support in different areas of your life?

I often fall into the trap of conflating ongoing “help” with specific “support” needed to achieve a particular goal or overcome a challenge. The support could be financial, technical, creative, or even emotional. It’s an underlying problem that massively limits people’s potential in schools, workplaces, and other relationships.

I’ve been trying to find a name for this more focused, temporary support. Then I read

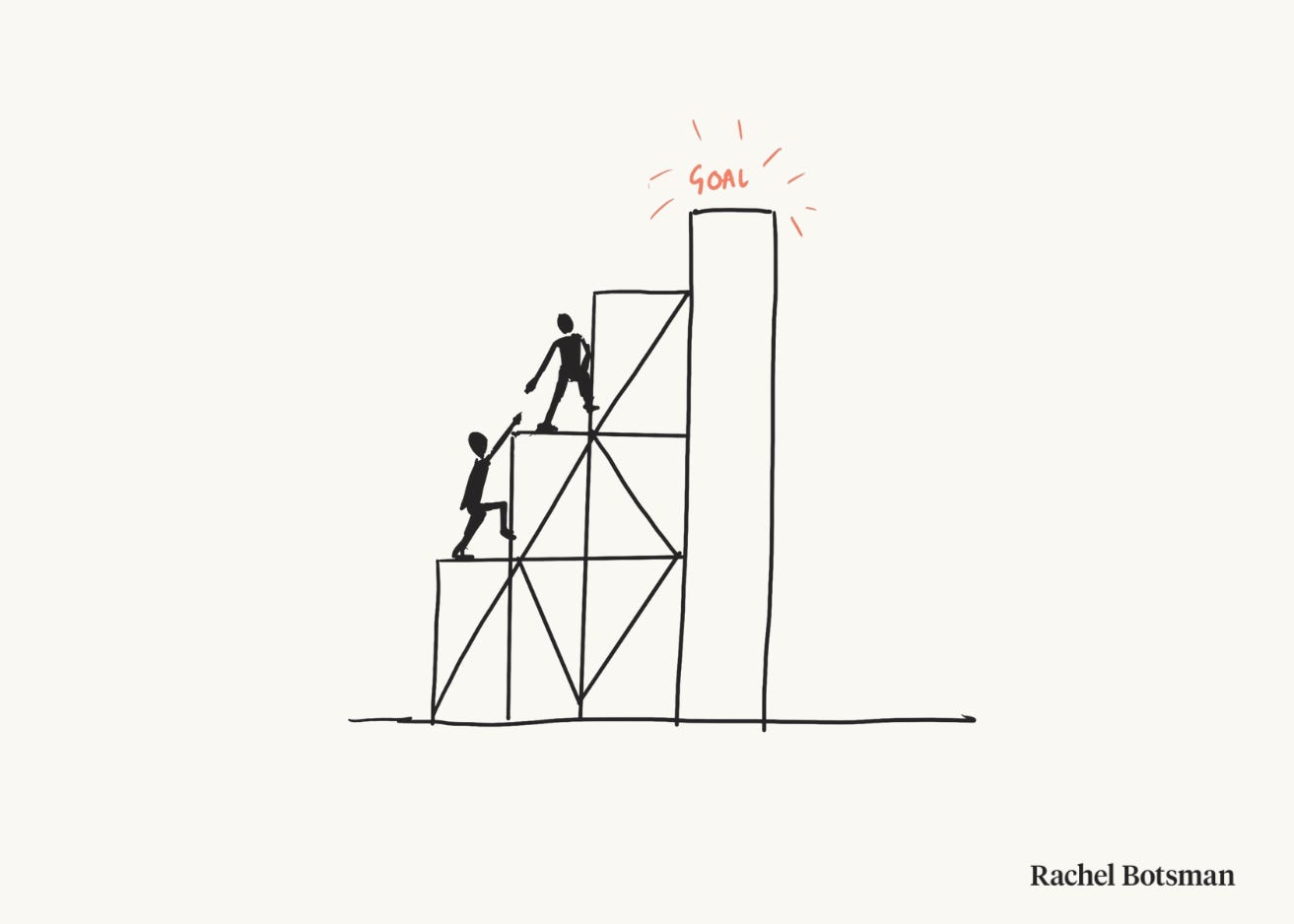

’s fascinating new book, Hidden Potential. He calls it “scaffolding.” Boom, that’s it! The concept has stuck with me – read on to find out how to use ‘scaffolding’ to find and provide support in your life and work.The construction of meaningful support

When we recently had our house rebuilt (not to be repeated), I thought the scaffolding that went up was quite beautiful (I know, a bit odd.) It was a temporary structure that enabled the builders to safely scale to heights out of their reach. They’d climb up and down the ladders in rain or sunshine without much thought. When the project was complete after 18 months, the scaffolding was taken down within hours. From that point forward, our home has stood, thankfully, on its own.

The scaffolding we use in construction is a beautiful metaphor for the support we need in learning or achieving new things.

As Adam Grant writes in Hidden Potential:

“Many new skills don’t come with a manual, and steeper hills often require a lift. That lift comes in the form of scaffolding: a temporary support structure that enables us to scale height that we couldn’t reach on our own.”

Think of something you’re trying to achieve in your life. It could be related to a specific goal or a change you want to make. For example:

Maybe it’s a creative project like writing a book.

Perhaps it’s tied to a physical goal.

It could be learning something like a new language or an instrument.

Or maybe it’s vastly improving a skill or habit, like managing finances.

Would any of the above happen with general help? Maybe, but more likely, no. We need a scaffold!

Pop-up structures for motivation

Scaffolds are not permanent help structures; they are the right kind of temporary support that helps to get us going and gives us the skills and systems to keep going. I think of them as ‘pop-up’ structures for motivation.

Side note: Interestingly, the Latin equivalent of the noun ‘support’ is firmamentum, which means ‘prop.’ Not to hold or help.

The concept of scaffolding was first introduced by the late Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky and later developed in the 1970s to help teachers understand how to help the learner best. But it is also a valuable way to provide support systems for problems and challenges at work.

Four key features of an effective scaffold

A great support person knows how to offer initial instruction, put a practice or system in place, and then remove the scaffold just like the builders.

In Hidden Potential, Adam identifies four critical features of scaffolding:

Scaffolding generally comes from other people.

Scaffolding is tailored to the obstacles in your path.

Scaffolding comes at a pivotal point in time.

Scaffolding is temporary.

3 and 4 are key. We may need to feel stuck - to have hit an obstacle or felt our limits. We may need to be running out of fuel. We may need to have taken the wrong path (s). We may have struggled to find motivation or time in the daily grind. In such moments, it’s hard to do it alone. We need a lift, foothold, or boost to find our way, gain momentum, or climb higher.

As Adam explains:

“It (scaffold) unleashes hidden potential by helping us forge paths we couldn’t otherwise see. It enables us to find motivation in the daily grind, gain momentum in the face of stagnation, and turn difficulties and doubts into sources of strength.”

Think of all the different ways we can put scaffolding to good use in our workplaces. Think of how many teams, projects and potential are blocked just by needing the right kind of support.

Build the right scaffolds

Looping back to my opening question: ‘Do you invest enough time in looking for the right kind of support in different areas of your life?’

I haven’t, and it’s something I’m going to change moving forward. What I’ve realised is scaffolds come in different forms. It could be a friend or colleague with a specific skill. A specialised freelancer who’s not just skilled but familiar with the problem. Or a more traditional mentor, teacher, trainer, advisor, or coach.

Here is something I’m thinking about that I hope is helpful for you:

When I’m stuck on something important, what scaffold do I need?

Is it within my network, or should I look further for proper guidance or advice?

What temporary structure will allow me to keep moving forward on my own?

Scaffolding is often not handed to us; we must seek it and assemble it ourselves. However, the more we experience the power of building a scaffold around a project or problem, the better we get at asking for it again.

Qu: Where would you benefit from a scaffold in your own life? What would this look like? Please leave your thoughts in the comments below.

Warmly,

This is SO just in time. Thank you.

Yes, scaffolding was the concept in Adam’s new book that drew my attention as well. Interesting about the Latin roots of the word