Resting is our work-life’s equal partner

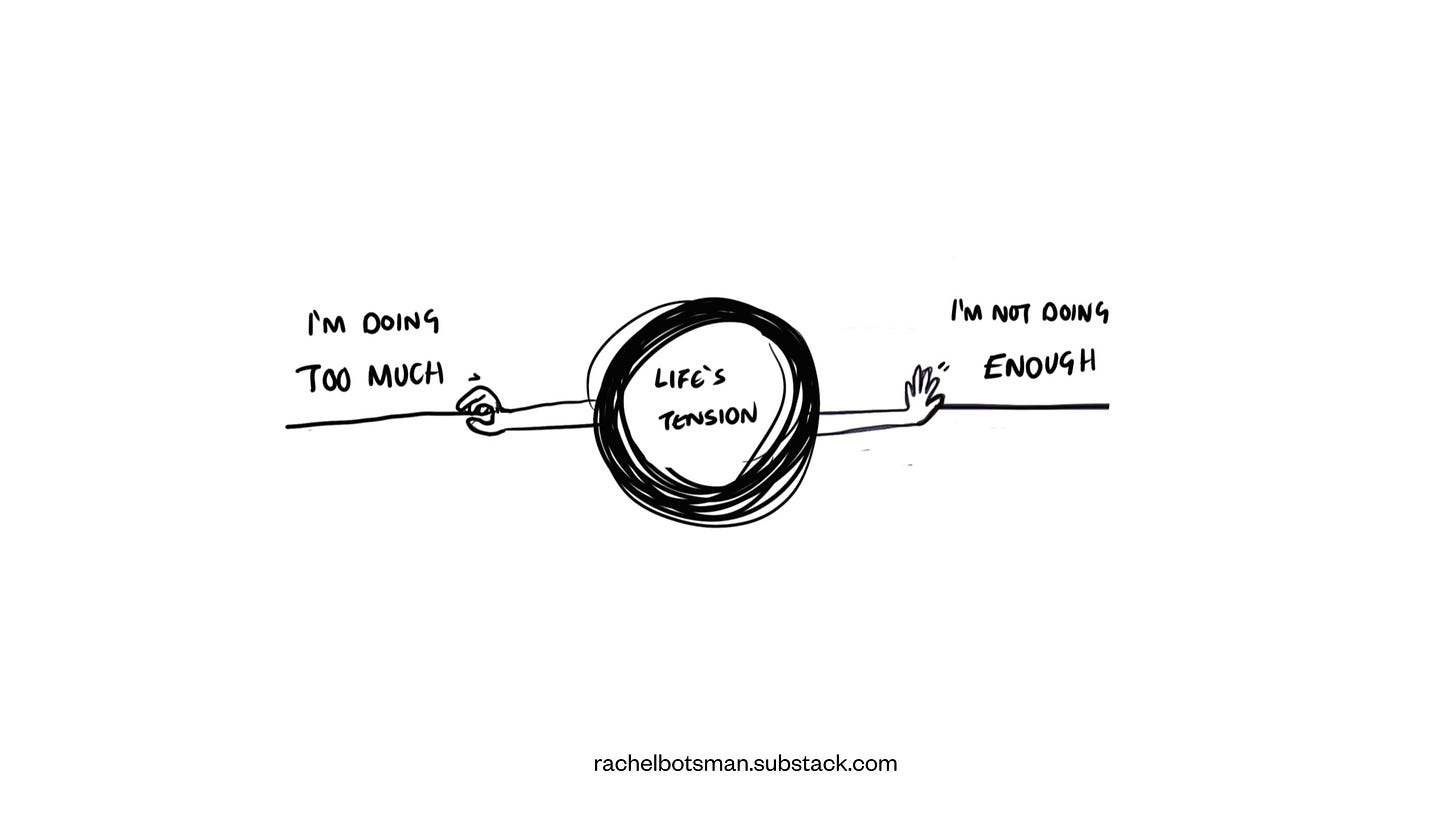

Do you struggle with the tension between not doing enough and doing too much?

Dear Rethinkers,

This week’s newsletter is about a topic I’m not very good at – resting without guilt!

More below after a quick weekly Rethink Recap:

Comment of the week comes from Emma Jarman in response to Rediscovering a Beginners Mind. She pointed out the work of psychiatrist Ian Gilchrist who blows up misconceptions about our ‘divided brain’.

An interesting report came out last week from Gallup that surveys 160,000 employees globally on how engaged they are at work. (Reportedly, only 23% of workers are engaged.) This is a HUGE problem I’ll be exploring in my Future of Trust and Work series, exclusively for paid subscribers.

And a warm welcome to all our new Rethinkers. Please say hello and introduce yourself here 😊

If you read this newsletter every week and value the work that goes into it, consider becoming a paid subscriber for extra benefits.

I estimate I spend approximately 0.5% of my day just resting (not including my night’s sleep). Yes, I could use my young kids and job (and full-time study!) as an excuse but when I’m honest, it’s because I feel guilty about resting. There is always something I could be doing.

“When a dog lies in the sun, I imagine it does it without guilt, because as far as I can tell dogs seem more in tune with their own needs.” – Matt Haig, The Comfort Book

I love this quote. I never once look at my Labrador sleeping and think, “You’re so lazy, get up.” The opposite: I feel jealous. So why do so many of us struggle with the concept of “resting?” Not sleeping, or lying on the sofa in a Netflix binge, but simply sitting with our thoughts and doubts.

Our modern obsession with pace and productivity results in many of us treating rest like a guilty act, not the forge of creativity. Rest isn’t a priority in how we spend our days and that’s a systemic problem.

In the groundbreaking book Finding Flow by the psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, unpacked a fascinating question: Where does our time go in the day?

Based on activities reported by adults and teenagers across the US, Csikszentmihalyi compiled the percentages of how we spend our waking hours every day. He categorized that time into three types of “activities”:

Productive: Activities we do to “generate energy” for survival. Nowadays, this is almost synonymous with working or studying to ultimately make money.

Maintenance: Keeping things we have (mainly our body and possessions) in good shape or keeping them from falling apart, depending on how you look at it.

Leisure: What we do with the “free time” left over — from exercising, to being with friends.

It’s important to keep in mind that the research was done in the early ‘90s, pre-social media scrolling; however, by and large, the numbers build a revealing picture of what an average day looks like. (If you’d like to dig deeper, here is a 2020 study on what we do all day and some up-to-date data on time usage from the Center for Time Use)

A few things came to mind while I was looking at Csikszentmihalyi data:

To get better at resting, we need to address our very notion of time. Think of how a calendar is presented. The weeks and months are in linear straight-line blocks. But our lives are not linear and definitely not straight, as we tend to imagine. They are cyclical.

Each day’s cycle is basically made up of four parts — production, consumption, interaction, and rest. However, we only spend 3% to 5% of that cycle resting.

When are we taught how to not do something?

I started to wonder during the pandemic if rest isn’t a priority because society incorrectly measures success by outward signs — where we live, what we’re paid, our title, and so on.

Or does it come from the fact that we’re constantly taught how to do things from a young age? How to make decisions, take actions, and run from one thing to the next. We learn and pick up cultural cues from kindergarten on how not to rest. Just look at a child’s school timetable. It’s jammed!

When are we taught how not to do things?

When are we taught the benefits of inaction?

When are we taught to respect our bodies’ signals that we need to rest?

When are we taught what being passive and receptive even looks like?

It’s no wonder so many of us struggle with the tension between not doing enough and doing too much.

Get more from Rethink

Below for paid subscribers: the principles that have helped me rethink rest, and some recommendations for further exploration…

1. Do not do more today than you can completely recover from today. Do not do more this week than you can completely recover from this week.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Rethink with Rachel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.