Rethink: What makes shared understanding possible?

How learning to see begins with learning to name

Dear Rethinkers,

Elephant’s Breath. I painted the front room in our home this uplifting, earthy grey with a hint of magnolia. It was either that or Dead Salmon.

“To me, naming a paint can be as important as the colour itself,” says Joa Studholme, who for over 25 years has given Farrow & Ball paints their eccentric names from the kitchen table of her English countryside home.

From a young age, I’ve had a long-standing fascination with Pantone colour chips and paint cards. There’s something about the uniform grids of coloured rectangles or squares against a white background that I find oddly mesmerising (and relaxing). They feel like both a system and sensation at once.

When I was in Paris recently, I was lucky enough to see a show by Gerhard Richter. When he first exhibited his Color Chart paintings in Munich in 1966, audiences didn’t know what to make of them. Not a single work sold. As someone slightly obsessed with taxonomies and visual systems of nomenclature, I could stare at these paintings for hours. But they also sit right at the heart of how we understand one another: our shared frames of reference.

I know Elephant’s Breath is a rather silly name, but it works. It sticks. And in many ways, finding the perfect name for something — your project, your pet, a book, a nickname, even an email subject line — is an act of care, even love. It says: I see you. I understand you.

I know for me that when my work finds the right name, it becomes a way in for other people. A shorthand access point to the many ideas and feelings I’m trying to convey.

So the question I’ve been thinking about this month is:

Does learning to see and understand each other begin with learning to name?

“Finding the words is another step in learning to see.”

Botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote these words in Gathering Moss, a beautiful book about the mysterious world of 22,000 known species of moss. (I know it sounds a bit geeky, but it’s a lovely book to cozy up with in winter.)

The more carefully we name, classify, or describe something we see, the more fully it comes into focus — whether we’re studying nature, making art, or trying to navigate everyday life. Getting the label or definition just right might seem like putting something in a neat box, but often it does the opposite. It expands our shared frames of reference.

This question — does learning to see begin with learning to name? — isn’t new at all. Long before Pantone codes or paint charts, an 18th-century geologist was grappling with a deceptively simple problem: how do we know we’re seeing the same thing?

When colour needed a common language

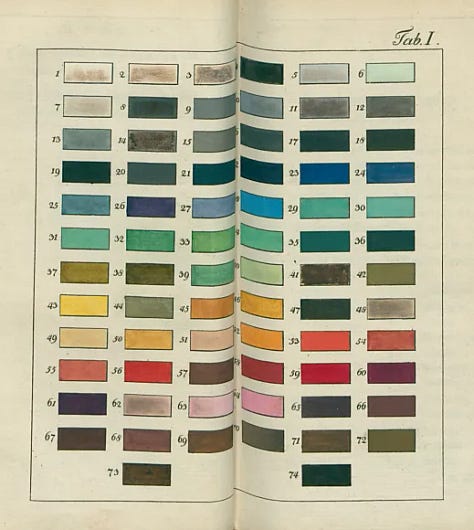

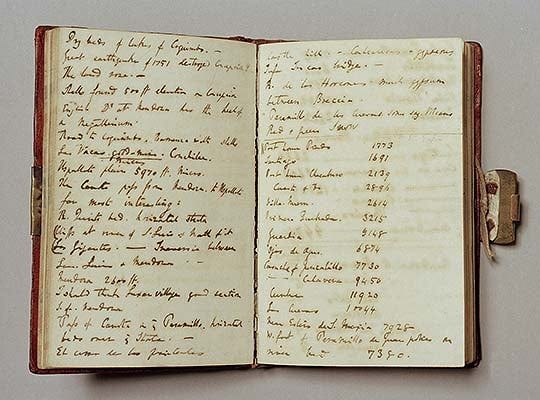

In 1774, the pioneering German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner published a dense academic text on fossils. Buried inside it was something profound: a systematic and consistent way of naming colour. Nothing like it had existed before.

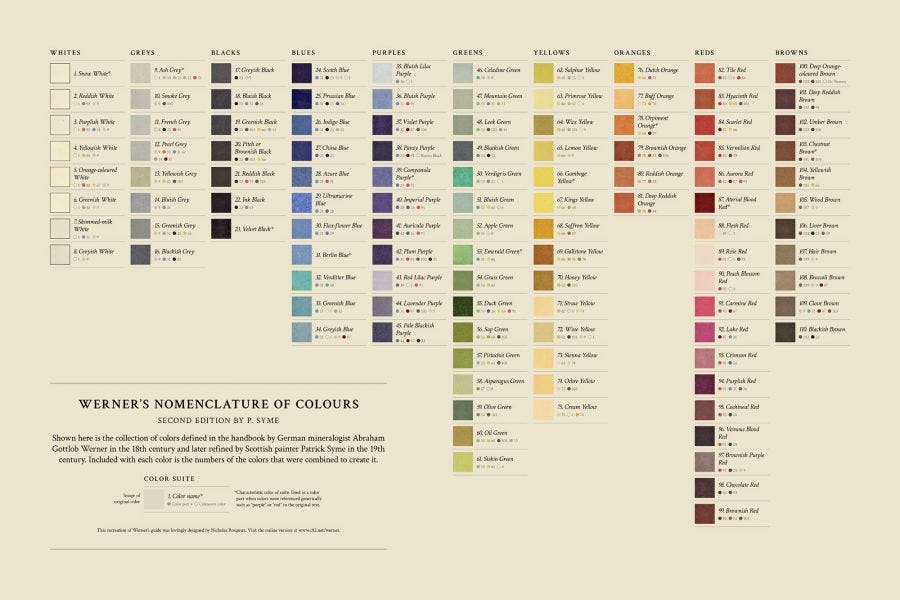

Snow White. Arterial Blood Red. Broccoli Brown. Sap Green. Although his goal was scientific (a common language for identification), the result reads almost like poetry. For the first time, scientists, artists, and naturalists could describe the visible world with shared meaning.

As Werner himself wrote:

“It is singular that a thing so obviously useful, and in the description of objects of natural history and the arts, where colour is an object indispensably necessary, should have been so long overlooked.”

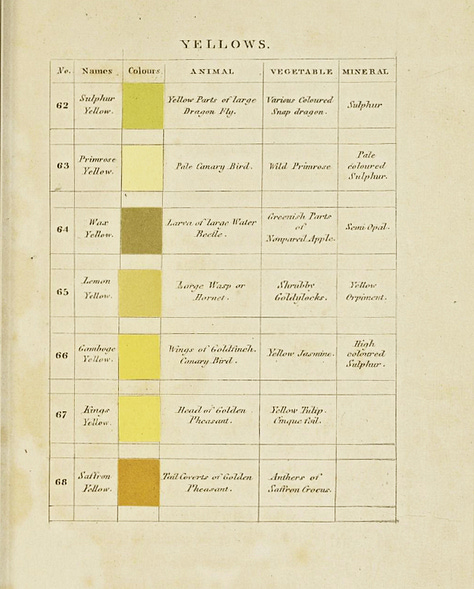

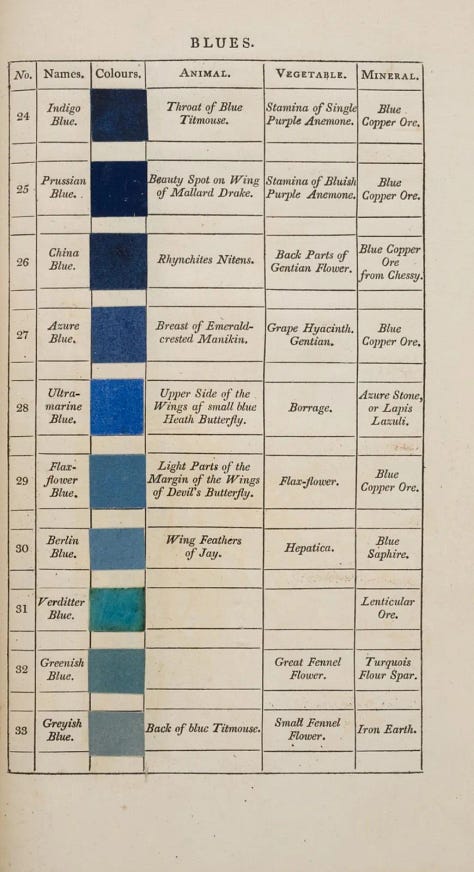

In a pre-photographic age, Werner’s scheme became the first field classification guide to the art of seeing. It was further developed some three decades later by the Scottish flower painter Patrick Syme. He identified 110 distinct tints, grouped into colour families, and for each one offered elegant, handwritten descriptions drawn from the natural world — animals, plants, and minerals sharing the same shade.

For example, “skimmed-milk white,” or No. 7, is described as “snow white mixed with a little Berlin blue ash grey.” You can find it, Syme notes, in “the white of the human eyeballs,” or in opals.

What struck me was how relational the system becomes under Syme’s touch. Colour isn’t abstract or numeric; it’s anchored in shared feeling or experience.

The result was Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours: Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy, and the Arts, first published in 1814. Designer Nicholas Rougeux has since created a beautiful online, interactive version of the book, which I’d highly recommend exploring. Nicholas shares my fascination with restoring and breathing new life into classic visual artefacts, not as nostalgia, but as living systems of thought.

Before data, there was description

Werner’s Nomenclature wasn’t just a system for recording observation, but for reaching agreement — yes, we are seeing the same thing. It was embraced by artists and scientists alike, including Charles Darwin, who took a copy with him on his 1831 voyage aboard the HMS Beagle. Describing the sea, Darwin wrote that the water was “indigo with a little azure blue,” while the cuttlefish moving beneath the surface appeared as “Berlin blue clouds varying in tint between hyacinth red and chestnut brown.”

Long before sensors, pixels, or code, seeing clearly depended on something far more fragile and human: the ability to describe what we noticed in ways others could recognise.

The Rethink moment

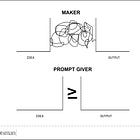

I’m drawn to artefacts from the past that help us reclaim human ways of thinking in a digital world. Werner’s nomenclature is a reminder that shared understanding is never quick, automatic, or programmed. Colour, texture, form, and movement have to be seen, experienced, and then named through a common language.

There are many things you would never assume are the same colour - a mushroom, a river stone, an old wool coat -until you look closely and realise they are. But that recognition requires care and attention. It can’t be arrived at through Google image searches or prompts alone.

In a world increasingly organised by systems that see, rank, and label for us, the quiet antidote may be this:

Take time to observe, notice, and describe the world around you.

Treat naming as an act of care and understanding—whether it’s a paint colour, your cat, or your next big idea. 🙂

Over to you:

What’s one thing you can notice and name today by slowing down just a little?

Warmly,

You might also enjoy:

From the archive

“To name something is to own it,” or “to know something you must name it” may be fictions that allow or rational mind to limit us to what it knows and understands.

Perhaps we should learn to look at things beyond what we can name or consciously know. That might open us to the wonder and power of the beginners mind, beyond the cage of reality constructed by our prefrontal cortex.

It doesn't answer the question, but your thoughts and excursions show me why communication and the collective, the “we” in terms of transformation in a business context, is not working as desired: We constantly talk about “speaking one language” – but quite obviously don't see the same thing in it.

So before language, the question is: What do I actually see? And then: How does X describe it? How do I describe it? Do we see the same thing but use different words? Do we see something different?

At the same time, I notice that ‘speaking one language’ is often understood as egalitarianism. That individuality, regional and cultural characteristics are not taken into account – or at least that is a concern. Ha! I will continue to think about this! Thank you!